In early 2023 the BRP was awarded funding from the Castle Studies Trust to undertake a series of non-invasive surveys to provide additional context to the outworks of Bamburgh Castle, focussing on St Oswald’s Gate and the Tower of Elmund’s Well. You can find out more about this area in our earlier blog posts (here’s a good place to start: Director’s End of Season Excavation Round-up).

We are now finalising the associated reports and sharing these ahead of releasing our interim excavation report. The next report we are sharing details a geophysical survey that we undertook with Dr Kristian Strutt of the Archaeological Prospection Services Southampton University exploring the environs of Bamburgh Castle.

Dominic Barker using the Bartington Grad 601-2 instrument on the Cricket Ground (photo: K. Strutt)

The Geophysical Survey Results

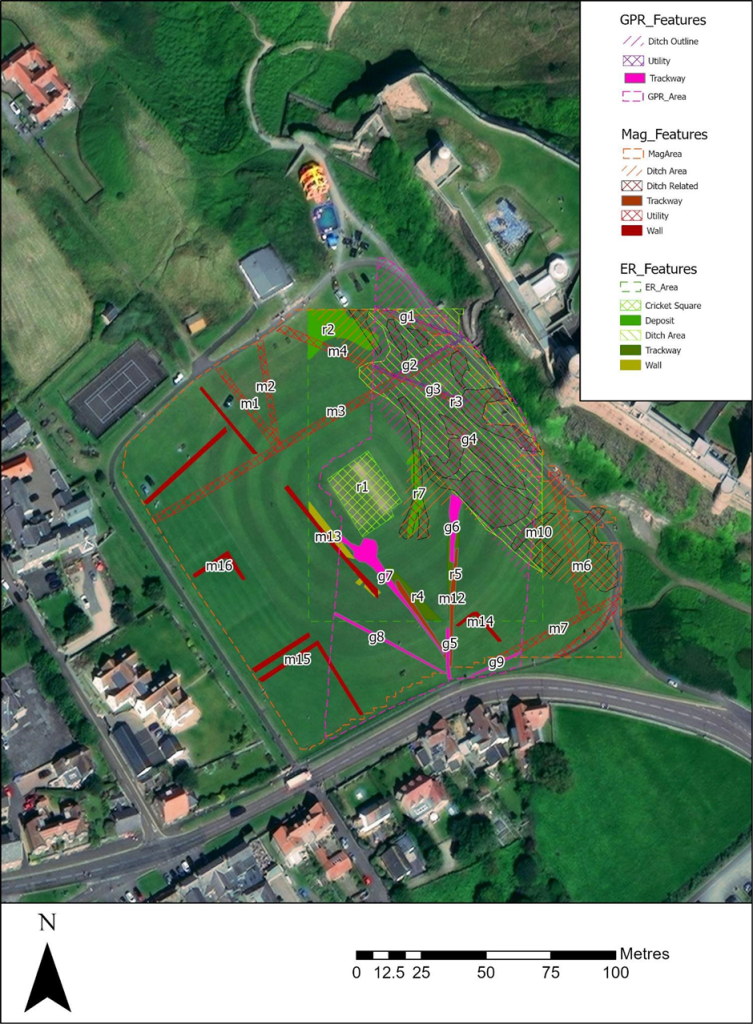

The survey utilised magnetometry, resistivity and Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) survey of areas of the Cricket Ground to the west of Bamburgh Castle. The results indicate the possible presence of a large ditch, some 45m across, immediately to the west of the outcrop, in addition to trackways, walls and other features in the survey area.

One of the principal questions we were hoping to address with the geophysics was if the castle ditch extended across the sports field at the base of the castle rock. A ditch cut through sandstone, can been traced in the area of the modern entrance that is at the site of the 12th century gate. This feature extends across the front of the castle as far as the sandstone ridge was present above ground. The results of the GPR do seem to strongly indicate a large feature in the area where we would anticipate the castle ditch to be and the magnetometry and resistance surveys do seem to support this. It is intended to conduct further fieldwork, starting with coring, to confirm this.

Earth resistance survey being carried out by BRP volunteers (photo: K. Strutt)

In addition, to the probable ditch feature, several features seen on the 1st Edition Ordnance Survey appear to be picked up on the surveys. Two trackways are evident, that lead to St Oswald’s Gate and to a cleft in the castle rock called the ‘Miller’s Nick’, which allowed people to scramble up to the West Ward in the 19th century. The second is an S-shaped path that meandered towards the area of St Oswald’s Gate, perhaps originally skirting around the edge of the ditch feature. One further route-way or path extends across the field parallel to the road in the village to the south, called the Wynding, that appears from records to have had a medieval origin. This path runs alongside a linear plot boundary and field boundaries and it will be interesting to see if more can be made from a number of anomalies that can be seen within the enclosure areas to the south and west of the plot.

The resistivity and ground penetrating radar surveys so far cover a more limited area, due to time constraints and public access. There is an area of low resistance that lies in just the area that the ditch would lie and matches up to the path towards the Miller’s Nick. The enclosure areas picked up in the magnetometry to the south-west also seems to be present on the resistivity. Notably, there is a high resistance feature that the S-shaped pathway may curve deliberately to avoid at the south part of the plot. A further T-shaped high resistance feature is present in the north-east extending from the area of the modern pavilion that will bear further study. The GPR further reinforces the presence of some of these features and indicates some depth to the anomaly that is interpreted as the ditch, though the signal attenuates before it could indicate a true depth.

Interpretation plot of all three surveys, labels link to the report text (Airbus 11/05/23)

Download the Full Report

If you want to take a deeper dive into the results of the geophysical survey you can download the report here: Report on the Geophysical Survey at Bamburgh, Northumberland, July 2023

It provides more information about the background to the site, detail about each survey technique and a breakdown, with useful maps and figures, about what was discovered.

In our forthcoming interim report we use this information to enhance our understanding of the castle within its landscape context and explore in more detail what some of the features identified in the survey might be.

The geophysical survey described in this blog has been funded by the Castle Studies Trust.

This charity is entirely reliant on donations from the public. To help the Trust to continue funding this kind of research, please visit https://www.castlestudiestrust.org/Donate

To find out more about the Trust please visit www.castlestudiestrust.org