The last week of the season was a whirlwind! We had multiple specialists on site as well as representatives from various heritage and environmental institutional bodies, and we had to make sure everything was recorded and packed away for the off-season.

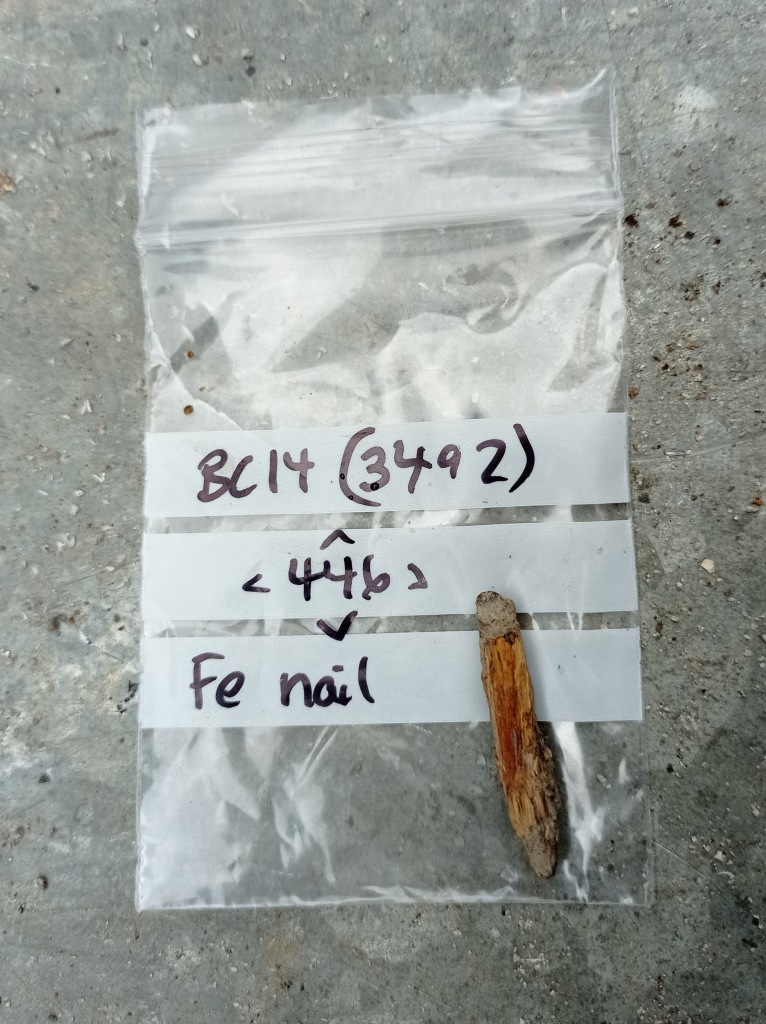

In finds, Margot’s team repacked artefacts taken out for student and visiting scholar research, ensuring they were still in superb condition (monitoring humidity strips and changing silica gel specifically) and not showing any signs of degradation. The probable gaming piece below left was used as an example for pitching a new exhibit of currently-off-display finds to the castle team. The finds bags in the middle were a few examples of melon beads selected from a large quantity we pulled for our student Helena to examine for her independent glass bead research. On the right, you can see our massive collection of single stycas…this doesn’t even include the hoard! A coin expert joined us one afternoon, so we moved the solo stycas temporarily into a context tray so they could flip through them easily in context order.

The students working with environmental sorted through a number of backlogged samples that had been floated, inventoried the storage areas, and moved all recent sorted samples into new boxes. We’ve created a new box system for environmental material, as it is usually one of the first categories of materials to get moved around by castle staff in their regular custodial and care-taking duties. New filing systems don’t sound super interesting when we put it like that, but it’s vital to meticulously manage and track our environmental archive. It also means new spreadsheets are afoot! We pulled all the newly-dried flots that fit the parameters of Alice Wolff’s archaeobotanical PhD studies, which we discussed here and here. And lastly cleaned the flot tank out one final time!

Out on the green at the base of the castle, our colleagues Kris Strutt and Dom Barker from Southampton continued to teach our students to gather data via resistivity, magnetometry, and GPR. Kris also popped into the Inner Ward to see if he could record any usable data in the highly-disturbed area at the top of the mount, while Dom explored one of the fields adjacent to our medieval harbour. We have preliminary readouts of the surveys, but our analysis is not quite complete. When Kris and Dom finish their current assignment (and have a few days to rest from all that walking), we will reconnect with them, better articulate what we were seeing, and ideally identify the various anomalies.

We also welcomed two guest specialists to our open trenches! Peter Ryder, a medieval buildings expert, spent the day poking and pondering about the multiple phases of masonry we have in the outworks. We hope to have an update on his findings in the near future. Tony Liddell, a photogrammetry expert, joined us to take high-resolution, overlapping photos of our trenches to create 3D models. Both of these consultations were made possible due to our funding support from Castle Studies Trust.

Finally in the trenches, we extended 5D, 5E, and 5F before recording them and closing them. Our blocked entranceway (5D) was extended towards the Victorian stairs to what we had been calling the postern gate. We uncovered rubble under the foliage and then a gentle slope of earth. 5E, between the two medieval walls, revealed more pavement of flagstones and cobbles. Trench 5F, for some reason referred to as “Betty” by the students, gave us access to more of the façade of the tower but we only brought it down to the top of the windblown sand layer first seen in last week’s round-up.

We also removed some more rubble from the well room, which has still not been bottomed-out. The paparazzi did catch this rare photo of Claire Watson-Armstrong, and we were so excited to have her on site! She has been a vocal supporter of our work, and it meant a lot for us all to see her having a blast on the hunt for the medieval well.

Thank you so much for following along this season! We appreciate your patience getting this final update posted, as we all went our separate ways Saturday morning and immediately back to our day jobs on Monday. We’ve gotten a chance to breathe and organise our thoughts, so expect more content over the next few weeks: Graeme’s season round-up, our masonry theories, 3D models, and our geophys interpretation. Finally, thanks again to Castle Studies Trust who supported us in our endeavours this season. You can read all about the work we were able to undertake so far from their generous grant at this link, and updates on on our results will also be accessible from there in addition to the main blog page.

And don’t forget about our post-ex week the 10th through 14th of September! We would love to see new and old faces there as we focus on finds processing, identification, and analysis!